The Oratory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

by Gary Kaplan

Oratory is the most demanding of the arts. It requires not just presentation, like painting or writing. It goes beyond presentation to demand audience response. Music has rhythm and harmony, painting has color and form, but oratory has only words and the human voice to work the magic of persuasion and inspiration.

Prominent among orators of recent memory was the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s oratory was a unique fusion of the elevated and the vernacular, the secular and the sacred. His most famous speech is I have a Dream from the March on Washington in 1963. We can still hear in the listening booth of memory the rising and then abruptly falling cadence of his stirring peroration: “Free at last, free at last, thank God almighty we’re free at last.” If all art aspires to the condition of music, that masterpiece of oratorical art reaches the goal.

But another speech deserves our attention at least as much. That is the speech he delivered on April 3, 1968, in Memphis, in support of the sanitation workers’ strike. It is known as the “I’ve been to the Mountaintop” speech.

He had not called the strike, but the violence that erupted around it had made it a national issue. He had been asked by the other civil rights leaders to come. There was a need for both persuasion, to continue the campaign, and inspiration, to believe in its eventual success. King turned to his favored fusion of sacred and secular, the Bible and the vernacular. For this occasion, he drew on the culminating event of the Old Testament: the farewell and death of Moses.

He sets the scene with a historical parable:

“If I were standing at the beginning of time… and the Almighty said to me, ‘Martin Luther King, which age would you like to live in?’ I would take my mental flight by Egypt… across the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the promised land.”

He continues, touching down in every period of history and finally arriving in his own time, the second half of the 20th Century, a time when “trouble is in the land.”

It wasn’t the first time he had invoked the flight from Egypt as the paradigm of the struggle for freedom and justice. Biblical echoes abound in his speeches. But this speech is particularly rich in references, and many of them come from the last six chapters of Deuteronomy, the culmination of the first recorded escape from slavery to freedom.

His favored narrative structure is Mosaic: history, interpretation, exhortation, inspiration. It is also rhythmic. The speech continues, like many biblical chapters, with a recapitulation of the history and a restatement of the vital purpose of the present journey.

“The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land. Confusion all around. …we have been forced to … grapple with the problems that men have been trying to grapple with throughout history.… Survival demands that we grapple with them.”

Moses makes a similar appeal: “…this is not a trifling thing for you: it is your very life” (32:47).

The words define the stakes: It is a matter of survival; your very life.

King implores the people to stay together, referring again to Egypt: “… whenever Pharoah wanted to prolong … slavery …he kept the slaves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, … that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery. Now let us maintain unity.“

He echoes Moses again, this time from Exodus: “The issue is injustice. …God sent us by here to say…that you’re not treating his children right. … We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end…. We’ve got to see it through. Either we go up together, or we go down together. “

He conflates the biblical and the actual: “It’s all right to talk about ‘streets flowing with milk and honey,’ but God has commanded us to be concerned about the slums down here, and his children who can’t eat three square meals a day.”

He invokes recent shared history: Birmingham, the 16th Street Baptist Church and the police dogs, singing We Shall Overcome in the paddy wagon and praying in jail…”and we won our struggle in Birmingham.”

The story of his stabbing is a prime example of his rhetorical virtuosity. In 1958 he was stabbed in the chest. It was reported in the news that if he had sneezed he would have bled to death. In this speech, he uses that anecdote as a rhetorical device, linking the personal with the historical to forge a rhythmically compelling narrative.

“And I want to say tonight… that I am happy that I didn’t sneeze. Because if I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around here in 1960, when students … started sitting in at lunch counters. And I knew that as they were sitting in, they were really standing up for the best in the American dream. And taking the whole nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. If I had sneezed, I wouldn’t have been around in 1962 … in Albany, Georgia…I wouldn’t have been here in 1963 … to tell America about a dream that I had had. … I’m so happy that I didn’t sneeze.”

The devices move the narrative. The repetition of “if I had sneezed”; the pairing of “sitting in” and “standing up”; the leap from lunch counter to “those great wells of democracy”; the rolling rhetorical thunder of history, interpretation, exhortation and inspiration.

Moving into his conclusion, he returns to the closing verses of Deuteronomy for a final grand fusion of the personal and the eschatological, the colloquial and the scriptural, the secular and the sacred.

He starts with the historical moment:

“Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now.”

Why doesn’t it matter? He explains:

“Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.”

And then the rising exhortation:

“And he’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land.”

And the final flourish of inspiration:

“And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man.

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

He could not have known it was his last public oration. The next day, April 4, he was shot dead at 6:05 PM on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel. He was 39.

Deuteronomy ends with majestic pathos as Moses sees the promised land from the mountaintop but dies without entering it.

“So Moses the servant of the Lord died there… Never again did there arise… a prophet like Moses….” (34:5/10).

Tomorrow, April 4, many voices will utter the same lament about Martin Luther King, Jr.

Header image citation:

“Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking at Mason Temple, Memphis, 1968” (2021). Sanitation Workers Strike, 1968. 75.

https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/speccoll-mss-mpressscimitar2/75

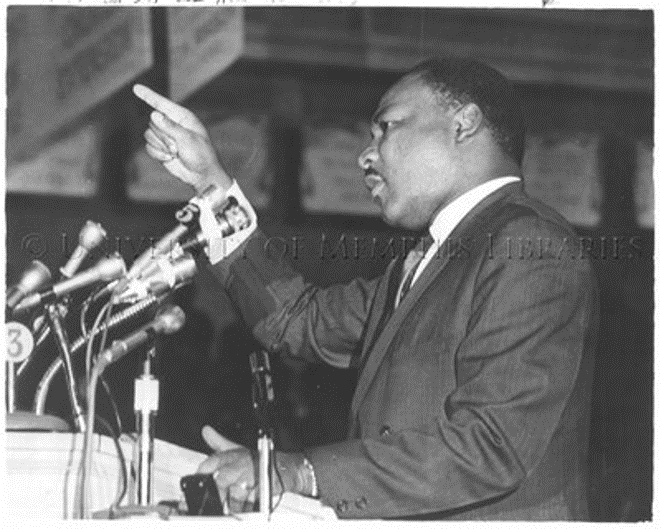

Body image citation:

“Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking at Mason Temple, Memphis, 1968” (2021). Sanitation Workers Strike, 1968. 77.

https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/speccoll-mss-mpressscimitar2/77

Gary Kaplan is the executive director of JFYNetWorks.

Other posts authored by Gary can be found here.

HOW ARE WE DOING? In our pursuit to serve up content that matters to you, we ask that you take a couple of minutes to let us know how we’re doing? Please click here to be navigated to our JFYNet Satisfaction Survey. Thank you!