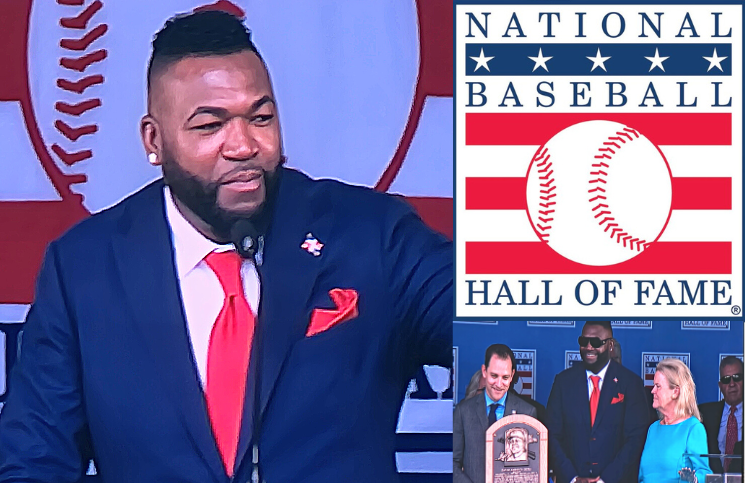

Last week, I ventured with a group of friends to Cooperstown, NY, on our first-ever pilgrimage to the Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony to see David Ortiz join the 1% of baseball players enshrined in the Hall. We expected to hear a wonderful and energetic speech from Big Papi. What we didn’t expect was life and history lessons with a reach far beyond the green fields of baseball.

Seven baseball players were inducted this year: Bud Fowler, Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso, Tony Oliva, Buck O’Neil, and David Ortiz. Each brought his own unique gifts to the game. Their induction ensures that their stories will be preserved forever. There was so much to learn.

All baseball fans know Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play Major League Baseball, but few know the name Bud Fowler, the first African American to play the game professionally before the creation of Major League Baseball. Fowler is the only player in the Hall of Fame ranks who was actually born in Cooperstown. As Hall of Famer, Dave Winfield explained in his remarks about Fowler, “There was something magical about this game that caught his eye and imagination, so much so that he’d spend the rest of his life playing and managing this game.”

As much as Fowler loved the game, the establishment of players and coaches did not love him. Their enmity was due to the color of his skin. He was constantly thrown at in the batter’s box, players slid into him at second base with their spikes high to injure him, and some opposing teams even refused to play unless he left the field.

Yet he kept competing, playing, and coaching for more than 50 teams during his lifetime (1858-1913). He created the first all-Black barnstorming team, the Page Fence Giants, and his efforts were crucial in laying the groundwork for the eventual creation of the Negro League, the only league in which African Americans were allowed to play the game from the 1920s until the late 1940s.

Buck O’Neil played in the Negro League. Today, it is unconscionable that the league was even necessary, but O’Neil always insisted not to feel sorry for the players who got to play the game they loved because the league existed. In 2005, 17 members of the Negro League were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, but O’Neil was not one of them, coming up just one vote short. Some would have been outraged about the irony of asking O’Neil to speak on behalf of the 17 during that induction weekend in 2006. But O’Neil embraced the moment, bringing his larger-than-life personality to the stage and speaking with passion for and about the players.

O’Neil died two months after that speech, sixteen years before he could see his own plaque hanging in the Hall. His niece, Dr. Angela Terry, summed up the moment quoting his own words: “Man, oh man, nothing could be better.”

Irene Hodges, daughter of Gil Hodges, told a story about one of her father’s teammates. “Nothing was more important to my dad than giving Jackie [Robinson] all of his support. We were like family with the Robinsons. Jackie’s kids played in our house. We played in theirs. My dad and Jackie were not only teammates, they were family,” she said. “During a game, Jackie was being heckled non-stop by the opposing dugout. At one point, my dad had had enough of that. He slammed his glove down, walked over to the top step of the dugout, and said, ‘If anyone else has anything to say, let them come out here right now, and we will settle it.’ Nobody came out and no one said another word.”

It’s easy to draw a line from Bud Fowler through Buck O’Neil and Gil Hodges straight to David Ortiz. While it should have been unnecessary, players like these paved the path for minority players. Ortiz acknowledged that even with all his talent, he would not have achieved his success if not for the support of other players, family, and fans. Even with his immense skills, he needed the courage and determination of those who came before him and those around him to become the Hall of Famer who will forever be revered as Big Papi.

These stories echo loudly in our schools and classrooms. For minority students, many who came before them fought so they could find equity in education. All students, no matter how intelligent, no matter how sharp their raw skills, need the support of family, teachers and peers in order to develop their true potential.

If this message was not clear early in Ortiz’s speech, he made it crystal clear as he approached the end.