The lonely path of innovation–Thinking Differently, Overcoming Obstacles

by Joan Reissman

This is Women’s History Month—a time to celebrate the accomplishments of women throughout history. Women have faced an uphill battle to establish themselves in many careers, especially in the field of science. Even today, women struggle to gain an equal foothold with their male counterparts. Science labs depend on grants, and obtaining grants is highly competitive. Despite the obstacles, many women have made significant contributions in science. Here are some examples.

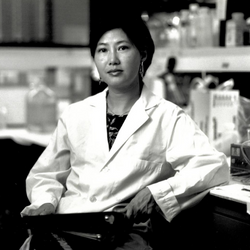

Flossie Wong-Staal, Ph.D. (1946-2020)

When people started contracting AIDS in the 1980s, most didn’t recover. Thanks to the research of virologist Dr. Flossie Wong- Staal, people today are living long lives with the disease.

Dr. Wong-Staal was born in Guangzhou, China, in 1946, but grew up in Hong Kong. She came to America to further her studies at UCLA, where she earned a B.S. in bacteriology and a Ph.D. in molecular biology.

After graduating from UCLA, Wong-Staal joined the National Cancer Institute and began her research with Dr. Robert Gallo on retroviruses (a type of virus that has RNA instead of DNA as its genetic material). Gallo and Wong-Staal noticed that the HLTV-III virus was present in patients with AIDS. This discovery led to the important conclusion that AIDS patients developed the disease from the transmission of HLTV-III. Another lab in Paris was also studying virus presence in AIDS patients. The two groups argued for credit, but the important thing was that this research laid the foundation for identifying and treating AIDS. Wong-Staal’s work was an essential part of this discovery because she cloned HIV and provided a genetic roadmap that helped scientists understand how the virus tricked the body’s immune system. This research helped develop drugs and other treatments. When the French lab won the Nobel Prize in 2008, many felt that Gallo and Wong-Staal also deserved recognition. Wong-Staal’s research helped scientists understand the connection between virus and disease. Her retrovirus research is still used today to uncover the mysteries of many diseases.

Source: Public Domain, National Cancer Institute, Creator: Bill Branson, https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=8247

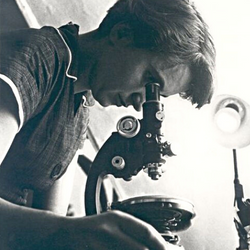

Rosalind Franklin (Ph.D.) (1920-1958)

Dr. Wong-Staal’s work would not have been possible without the groundbreaking work of Rosalind Franklin, whose famous x-ray (photo 51) identified the spherical structure of DNA. J. D. Bernal called her X-ray photographs of DNA “the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken.” Many historians feel that Franklin did not get the credit she deserved. Her biographer, Brenda Maddox, referred to Franklin as “the dark lady of DNA.”

Franklin was born in England. She showed scholastic abilities at an early age and attended the University of Cambridge. In 1941 she received honors from her final exams which qualified as bachelor’s degree credentials and made her eligible for research jobs. At that time, the University did not award degrees to women. Cambridge did finally award a degree to Franklin in 1947.

After a brief unsuccessful lab assignment Franklin became involved with the British World War II effort. Through her research, she improved the performance of coal as fuel and in gas masks. Her work helped the British war effort and became the basis of her Ph.D. dissertation at Cambridge in 1945.

After the war, Franklin worked in France for Jacques Mering. It was in Mering’s lab that she was introduced to X-ray diffraction. Her knowledge of X-rays would become the vehicle for her work on DNA.

Franklin moved back to England after she received a fellowship and began to work under the supervision of John Randall. Here she refined her observations of DNA structure through X-ray diffraction. Once she established the spherical structure of DNA (the famous photo 51) the evidence was available for Watson and Crick to develop the double-helix model which is still the basis of DNA research.

Franklin never knew that her supervisor had shown photo 51 to Watson and that these images helped Watson and Crick create their double helix model. In 1962, Watson, Crick and another researcher named Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize.

Franklin was not included in the award because she had died in 1958 and the Prize is not awarded posthumously. Crick did acknowledge Franklin’s contribution after her death, but many feel that her role in DNA research should receive more acknowledgment.

Source: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Source from the personal collection of Jenifer Glynn, 1955, Author: MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rosalind_Franklin.jpg

Sophia B. Jones, M.D. (1857-1932)

Careers in science for women would never have been possible without pioneers like Sophia Jones. Dr. Jones was born in Ontario in 1857. She was always interested in science but the University of Toronto’s medical school was not admitting women in her time. Jones was accepted at the University of Michigan, however, and she became the first Black woman to graduate from their medical school.

After graduation, Dr. Jones became the first Black faculty appointee at Spelman College in Atlanta. At Spelman Jones organized the first training program for Black nurses. After establishing the program at Spelman, Jones took a position at Wilberforce University in Ohio. She was the resident physician at the University but she also treated people in the community.

After many years of research, Dr. Jones published her findings under the title “Fifty Years of Negro Public Health” (1913) in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. This article was one of the first medical research pieces published by a Black woman.

Dr. Sophia Jones devoted her long career to public health. She was a passionate advocate for equitable health care for Black people, exposing racial barriers to health care. She practiced in many cities and improved access to medical care in Black communities.

Her words still resonate today:

-

“It is not too much to expect victory for a race, which, in fifty years, has reduced its illiteracy from an estimated percentage of 95 to 33.3 as given by the census figures of 1910. Let the teaching of general elementary physiology, including sex physiology, and sanitation be placed on a rational basis in all colored schools and colleges, in the hands of men and women thoroughly trained and with full knowledge of the health problems named above, and there can be little doubt that the issue of the conflict will be such a rapidly declining death rate and reduced morbidity as will astonish the civilized world” (Fifty Years of Negro Public Health.1913).

Source: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan, and the Heritage Project Archives. https://heritage.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2020/08/Sophia-B-Jones-MichMed-300×389.jpg, https://www.uofmhealth.org/history

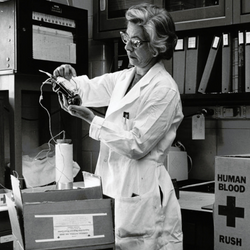

Sarah Stewart, Ph.D., M.D. (1905-1976)

Oncologists understand the link between viruses and certain types of cancer, but this knowledge would not have been possible without Sarah Stewart’s ground-breaking work in viral oncology. When teenagers receive an HPV vaccine, they should thank Sarah Stewart.

Sarah Stewart was born in Mexico in 1905. Even though her mother was born in Mexico, the Mexican government forced the family to leave during the Mexican Revolution because her father was an American.

Sarah graduated from New Mexico State University with a degree in Home Economics.

That may seem like an odd choice for a future doctor, but it was the best major open to women who wanted to take science courses at that time. Stewart had better opportunities for graduate work, and she received a Ph.D. in microbiology from the University of Chicago in 1939. She was the first woman to be awarded a medical degree from Georgetown University in 1949.

Today many teenagers receive an HPV vaccine to prevent infections that cause cancer, but when Stewart first asked for support to study the link between viruses and cancer, her application was rejected. After receiving her medical degree, she was able to obtain support for research in viral oncology.

Stewart worked with Dr. Bernice Eddy and their experiments showed that a virus produced 20 types of tumors in mice. This work gained attention and the Stewart-Eddy research was featured in a TIME cover story in 1959.

Sarah Stewart’s research changed the field of oncology. When she began her research, doctors and scientists thought the idea of a link between cancer and viruses was ludicrous. Stewart’s research proved that there was such a link.

After the FDA approved the HPV vaccine, there was a dramatic drop in deaths from cervical cancer. Doctors never thought there could be a connection between viruses and cancer because most cancers could not be transferred to another person like other diseases.

“Without Stewart and Eddy’s persistence, the HPV vaccine would never have happened,” according to Diana Pastrana of the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Public Domain: G.V. Hecht – NIH History Office on flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/historyatnih/32683550603/

Anna Mani, B.S. (1918-2001)

We take the science of weather prediction for granted, but we rely on scientific knowledge and instruments for weather. One of the people who helped bring a scientific focus to meteorology was Anna Mani.

Anna Mani was born in India in 1918. When Anna was eight, she did not want the customary gift of diamond earrings. Instead, she asked for an Encyclopedia Britannica set. Anna pursued her interest in academics and received a B.S. in physics and chemistry in 1939 from Presidency College in Madras. She then won a scholarship to the Imperial College in London. Although Mani authored many papers, she was not granted a Ph.D. because she did not have a master’s degree in physics.

Mani returned to India in 1948 and got a job with the meteorological department in Pune where she began her work with metrological instruments. She organized and classified the instruments and in 1953 Manni became the head of the department supervising 121 men– quite a feat for a woman in India during the 1950s.

Manni helped standardize weather instruments and also did innovative work in the field of solar energy. She established a lab that measured wind speed and solar energy. She was also instrumental in developing equipment to measure ozone levels. She was a visionary and not afraid to pursue her interests to advance science.

Mani’s work did not go unrecognized in India. She was promoted to Deputy Director General of the Indian Metrological Department in Delhi. She continued her work with alternative energy and should be given credit for India’s many solar and wind farms.

Source: World Meteorological Organization (WMO)

“Reproduction of short excerpts of WMO materials, figures and photographs on this website is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission provided that the original source is acknowledged.”

https://public.wmo.int/en/copyright#, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) International, https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/celebrating-pioneer-indian-meteorologist-anna-mani.

Kati Kariko, Ph.D. (1955- )

Who would have thought that the daughter of a butcher in Hungary would provide essential clues for the practical application of mRNA? Kati Kariko has pursued her career without tenured positions and consistent funding. Yet she persevered and kept seeking support for her research. Understanding mRNA will hopefully provide clues to fighting many diseases, including cancer.

Kati Kariko was born in a small Hungarian town in a house without water, a refrigerator, or electricity. Even though she grew up without modern conveniences, she still wanted to be a scientist. Kati did well in school and worked hard.

Eventually she earned a Ph.D. Kariko decided to move to the U.S. from Hungary with her husband and daughter for better opportunities. They sold their car on the black market and smuggled the money to support themselves by stuffing the cash in their daughter’s teddy bear.

This science pioneer has drifted from lab to lab, remained untenured and has never made more than $60,000 a year. Her work centers on mRNA. mRNA carries the genetic information to make proteins. Kariko’s idea was that since mRNA provides instructions, it could guide cells to make many types of medicines. Like many other pioneering ideas, this theory did not go along with established conventions, but the hope is that mRNA will help provide many vaccines for diseases like flu, AIDS and malaria.

Kariko has been researching mRNA since 1989 and has had many setbacks and failures. When her first project failed to treat blood clots, she was without a lab. Then she had a friendly conversation with Dr. Drew Weissman, a faculty member at University of Pennsylvania, that changed her life. Weissman was interested in RNA and hired Kariko. The two scientists began a partnership. At first, they were unable to harness the power of mRNA, but they eventually found a molecule that helped the mRNA work effectively. When Weissman and Kariko tried to publish their research on the relationship between RNA and immunity, scientific journals rejected the work. When the research was finally published in 2005 (Immunity, Volume 23, Issue 2) the article received little attention. Although Kariko and Weissman were frustrated, they formed their own company to investigate using mRNA to combat a wide range of diseases.

However, two new companies, BioNtech and Moderna, eventually noticed. BioNTech hired Kariko in 2013 and the two companies now fund Weissman and Kariko’s lab. BioNTech and Moderna funded Dr. Kariko’s and Dr. Weissman’s research efforts to use mRNA for a flu vaccine. Then came COVID and people were willing to try anything. After China published the first COVID genetic sequence, the biotech companies were able to make a trial vaccine in a matter of days. And what did Kati Kariko do to celebrate? She bought a box of Goobers.

Kati Kariko was happy. She said, “My dream was always that we develop something in the lab that helps people… I’ve satisfied my life’s dream” (New York Times 2/24/21).

Source: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International. Karikó Katalin 2021. május 21-én a Szegedi Tudományegyetem (kivágás). Date: 3 September 2021, Source: Own work, Author: Szegedi Tudományegyetem

This file has been extracted from another file: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karik%C3%B3_Katalin.jpg

Ellen Ochoa, Ph.D. (1958- )

Only two Hispanic women have logged hours in space. One of those women is Ellen Ochoa, the first Hispanic woman to go into space. She has made four space voyages and logged 1000 hours.

Ellen Ochoa was born in 1958 and grew up in California. When Ochoa was an undergraduate at UCLA she spoke to the head of the engineering department. He told her, “Well, we did have a woman come through here once, but it’s a really difficult course of study and I just don’t know that you’d be interested.” Not one to be discouraged, Ochoa went to the physics department where the department head was more encouraging. She received a B.S. in physics and then went on to obtain a doctorate from Stanford in electrical engineering.

Ochoa applied to NASA three times before she was accepted. Of course, that didn’t mean she automatically got a mission as an astronaut. NASA accepted her in 1990 and made her an astronaut in 1991. Ochoa’s engineering background was essential to NASA and she developed systems with computer optics. These systems helped computers “see things” and Ochoa’s computer optics system has proved useful for finding engine flaws and improving data capture of Rover missions.

After four space missions, Ochoa moved into management. Her worst day was in 2003 when the shuttle Columbia blew apart. That day Ochoa was in the office working as a liaison for mission control. Ochoa said, “It was the absolute worst thing that can ever happen. It was difficult personally, and for everybody that worked at NASA and their families.” She eventually became the Director of the Johnson Space Center. She was the first Hispanic and the second female director of the center.

Although many people discouraged Ochoa along her journey, she never gave up. Her tenacity made her successful. Even though she had to deal with people who didn’t think she should be there, she didn’t listen. Ellen Ochoa serves as a model for future female astronauts and scientists everywhere.

Source: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Description: Astronauta de la NASA. Ellen Ochoa. NASA astronaut, mission specialist. Date: Taken on 12 February 2002, Source: spacelight.nasa.gov, Author: NASA

Marie Maynard Daly, Ph.D. (1921-2003)

Do you know anyone with high cholesterol or high blood pressure? Tell them to thank Marie Daly for her work.

Marie Daly was born in New York City in 1923. She received a B.S. in chemistry at Queens College and became the first Black woman to receive a Chemistry Ph.D. in 1947, a time when only 2% of Black women had any college degrees. Her Ph.D. was from Columbia University.

During her years as a Ph.D. student, Daly became interested in amylase, a digestive enzyme. She taught at Howard University after completing her dissertation, but then she won a grant from the American Cancer Society. She worked on the order of amino acids in DNA and some of its structures. She later returned to Columbia as a biochemistry professor where she did her most important work. Daly worked with fellow professor Quentin Deming. Their research revealed the link between high blood pressure and cholesterol levels. They also found that there was a relationship between cholesterol levels and clogged arteries. Thanks to her work, scientists began to understand the relationship between diet and heart disease.

Marie Daly was committed to creating more opportunities outside of the lab. She honored her father, who was unable to complete his college chemistry program, by establishing a scholarship fund in his name for Black science students at Queens College. The next time you swallow a scrumptious slice of chocolate cake or dig into a crackling sack of potato chips, thank Marie Daly for making you feel guilty about it.

Source: Marie Daly, circa 1950s, The Rockefeller University. (n.d.). Daly, Marie M. Retrieved from Digital Commons @ RU: https://digitalcommons.rockefeller.edu/scientific-staff/10/.

Women’s history month prompts us to reflect on and celebrate women’s accomplishments. Without the strength and creativity of these female pioneers, we would be without some very important discoveries. Scientific innovation takes work and determination– and the ability to see things in a different light. Most of all, it takes passion and perseverance. I hope the examples of these courageous women scientists will inspire readers to believe in themselves and follow their own unbeaten paths.

Joan Reissman is a Learning Specialist with JFYNetWorks.

Other posts authored by Joan can be found here.

HOW ARE WE DOING? In our pursuit to serve up content that matters to you, we ask that you take a couple of minutes to let us know how we’re doing? Please click here to be navigated to our JFYNet Satisfaction Survey. Thank you!