Old Year, New Year, New Decade. Same Story.

by Gary Kaplan

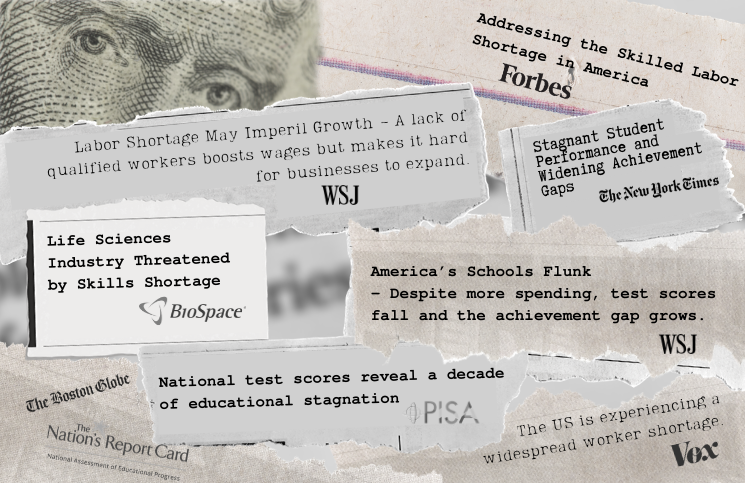

For readers of education and workforce journalism, the turn of the decade was neatly bracketed by two articles that summed up the year’s main themes: low student performance and labor shortage. First was a New York Times piece on December 28 headed “Year in Education: Stalled Test Scores…” Under the sub-head “Stagnant Student Performance and Widening Achievement Gaps” it reminded us that the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), our “gold standard” nationwide assessment, had found only one-third of fourth and eighth-graders proficient readers, while student achievement in both reading and math was flat over the past 10 years. That wasn’t all: the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), an 80-country international test under the auspices of OECD, found that American 15-year-olds have been stagnant in reading and math for two decades. Both tests noted widening achievement gaps between low-performing and high-performing students. The article did not delve into the demographics of the gaps, but we know all too well how that maps.

The new year opened with a workforce alarm in the January 6 Boston Globe headed “A worker shortage for life sciences.” The latest of many distress signals emanating from every corner of the labor market, it drilled down into the workforce development pipeline with a startling complaint from a quintessentially skill-intensive industry:

“At the associate degree and high school graduate level, job demand has grown by 140 percent with virtually no increase in supply.”

If it was surprising to learn that life sciences has any sub-PhD jobs, it was doubly puzzling that the industry should be seeing no increase in labor supply. A glance at population statistics quickly solved that puzzle.

Massachusetts is not a high-growth state. In the go-go years since the 2010 census we have added about 43,000 residents annually, a crowd that would occupy less than two-thirds of Gillette Stadium. High school graduation statistics are correspondingly modest: our graduating class has grown an average 358 more students per year over this decade. The 65,600 who graduated in 2018 would have been barely enough to fill the new jobs created that year—if they all went directly to work.

But high school graduation is not the complete workforce development story. In this economy, post-secondary education is the gateway to skilled employment. Here is where the complaint “no increase in supply” comes into sharper focus. The percent of high school graduates statewide going on to post-secondary education slipped from a high of 76.6% in 2013 to 72.3% in 2018 (latest data). That is the same percentage as in 2009. The gross number of college enrollees in 2018—49,092 —was down 2000 from the prior year and the same as in 2012.

We cannot support growing demand for skilled workers in the life sciences and other dynamic industries if we are not sending any more young people on to post-secondary education and training than we were in 2012. The documented lack of progress on national and international skill assessments shows that we are not building the foundational reading and math skills in K-12 needed to prepare for training in the higher-level skills our leading industries need.

Here in Massachusetts, our most relevant quality check on the skills of our workforce-in-training is the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System which starts in third grade and takes its final reading in 10th grade. What MCAS tells us is disquieting. There was no progress statewide on 10th grade MCAS scores in English and math from 2013 to 2018. Scores on the new MCAS 2.0, introduced in 10th grade last spring, are not comparable to the old test because of a new scoring system, but this new MCAS has been in place in the lower grades for three years. What’s the result? In 8th grade, a net gain of 2 points in English and a loss of 1 point in math. In 7th grade, a loss of 2 points in English and a gain of 1 point in math. (“Scores” are the percent of students reaching the top two of four performance levels.) Over three years of MCAS 2.0, no net gain at the threshold of high school. Test scores measure skills. Stagnant scores are not what dynamic, skill-hungry industries want to see.

And the achievement gaps that have bedeviled education and workforce watchers since the advent of standards-based data twenty years ago have not narrowed. On the contrary, the gaps between wealthy suburban school districts and poor urban districts almost doubled under the new 10th grade test. Considering the lopsided population distribution between suburbs and cities, we can expect to hear louder cries of “no increase in supply” from many industry sectors in the coming years.

Our economic future depends on a skilled workforce. K-12 public education, where 90% of our young people are groomed for the future, is our workforce development pipeline. Late-game strategies like early college, customized technical training and industry apprenticeships can help put the finishing touches on an emerging workforce, but only if the foundation of basic language and math skills is firmly in place. We need to start filling the K-12 pipeline at the bottom and keep it at capacity throughout its run. With negligible growth in total supply, we can’t afford any leaks if we want that pipeline to deliver the gusher of talent our thirsty economy needs.

Gary Kaplan is the executive director of JFYNetWorks.

Other posts authored by Gary Kaplan can be found here.

HOW ARE WE DOING? In our pursuit to serve up content that matters to you, we ask that you take a couple of minutes to let us know how we’re doing? Please click here to be navigated to our JFYNet Satisfaction Survey. Thank you!