AI disruption of working patterns is reaching into schools

Ever since the Bronze Age invention of the wheel, technological advance has disrupted patterns of human labor. Manual carriers of cargo were displaced by pullers of wheeled carts. Then oxen and horses displaced the human pullers. Then trucks displaced the horses. Now comes the form of artificial intelligence called generative AI.

Large language model computing is not just a sustaining innovation, in Clayton Christensen’s terms: it is a disruptive innovation. We’ve seen disruptive innovations before; but this one is going to be disruptive on a scale we have never seen, at least not since the wheel.

The computer, the “wheel” of the Digital Age, has caused a constant stream of disruptions. But this one is different. Generative AI, the technology behind ChatGPT, will displace jobs up and down the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (now called the O*NET). It will eliminate jobs at the top as well as the middle. Only jobs requiring physical presence and activity will escape. According to a sobering Wall Street Journal summary last week (AI Expected to Bring Gains in Output, Jobs Rethink, 8/29/23), all levels of education will be equally impacted.

A key difference between generative AI and previous disruptions is its invasiveness. It’s the kudzu of innovations. It penetrates every level of every industry. Even a change-resistant industry like education is being quickly overgrown. In the few months of generative AI’s career, schools have moved from blocking it to “embracing” it, as the New York Times recently put it (Schools Shift to Embrace ChatGPT, 8/26/23).

The reasons for AI’s invasiveness are its usefulness– new uses pop up every day; its ease—no special skill or training is required; and the low barrier to entry—with the ubiquity of computers in homes and schools, no investment in infrastructure is required. It’s as easy as an earlier innovation, electric light—just flip the switch. Or press the key.

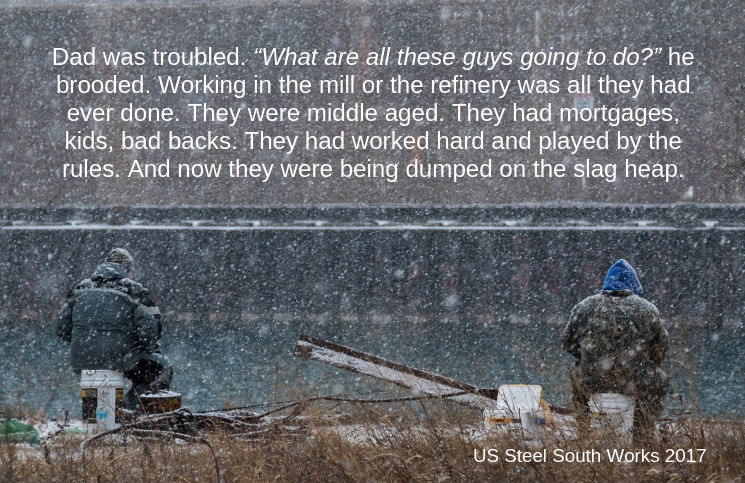

“Labor’s Twilight,” my elegy for the industrial age, was first posted for Labor Day 2018. It casts a burnished glow over the decline of the industrial Calumet Region where I grew up. Fondness for the old industrial order bleeds through in every ravishing photograph. Region nostalgia is something of a family affliction. The photographs are all from the studio of my cousin Matthew Kaplan, who has been witnessing and documenting the evolution (or devolution) of the Region since the 1970s. And my father, Jack Kaplan, is the oracle of working class abandonment.

My list of technological innovations, only five years old, reads like a quaint Montgomery Ward catalogue. AI was only a concept back then.

Despite the dark underpainting, the message of the piece is hopeful: Twilight can be dusk or dawn. In this age of generative AI, the labor value proposition is shifting even faster from implementation to innovation, from productivity to creativity. And it is clearer than ever that the knowledge and skills of our young people are the raw materials of our future.

It’s up to us to make sure this twilight is a dawn.

Gary Kaplan is the executive director of JFYNetWorks

Labor's Twilight

The Changing American Workforce

by Gary Kaplan | photos by Matthew Kaplan

In the 1800s the Calumet region of northwest Indiana was Chicago’s Cape Cod. The baltic blue crescent of Lake Michigan swung serenely eastward from the state line. Tawny beaches and rolling sand dunes offered refuge from the raucous, brawling city of the big shoulders. Windwarped swale and reedy marshland attracted hunters and fishermen, birdwatchers and botanists. The lowslung lakefront lured industrial land scouts.

In 1889, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company broke ground for a refinery on the lakeshore just east of the state line near a railroad junction called Whiting’s Siding. Within a few years the Whiting Refinery was the largest in the US. In 1906 J.P. Morgan and Judge Elbert Gary began construction on the US Steel Gary Works. By midcentury, the 20 miles of lakeshore between Chicago and Gary had filled in shoulder to shoulder with oil refineries, steel mills and chemical plants. The Calumet Region, named by 17th century French trappers for the marsh reeds (chalumet) that choked their canoe channels, had been transformed into the largest industrial concentration in the world.

Those industries needed labor. In the 1970s, heavy industry in the Calumet Region, collectively known as “the mills,” employed over 100,000 workers. Most of them belonged to unions. Their wages, benefits and pensions enabled them to own houses, raise families, buy cars, send children to college, and retire in their 60s with enough pension, savings and social security to live comfortably in their paid-off houses and enjoy their grandchildren for the balance of their 68 years of life expectancy. Their industrial union wages created a thriving economy. Their taxes built roads and schools, paid police and teachers and firemen. Settlement pushed south and east from the mill gates. By 1970 the Region’s population exceeded 770,000.

But things were changing

One morning in the 1970s my father slid onto the stool at the counter of his regular diner next to a friend who worked at Inland Steel. As they sipped their scalding coffee, the man told my dad that he was going to be laid off. The job he had done for twenty-five years was being “automated.” He was being replaced by a machine. It wasn’t the first instance of “automation,” but it was the first to hit so close to home.

Industrial labor was hard, dirty and dangerous. Steel-toed boots, asbestos gloves and hard hats were supposed to protect workers from the bubbling molten steel and hissing gas flares and toxic chemical fumes they tended all day long, and all night on third shifts. Those flimsy membranes didn’t prevent workers from losing fingers, getting hands crushed or being scarred by third degree burns when something erupted or burst or came crashing down. Occasionally a man would be killed. Billboards at the mill gates announced the number of days since the last industrial accident. Everyone knew that working in the mills was dangerous. But the pay and the job security were worth the risk.

No human activity has been more disruptive to the natural order than heavy industry, but none has produced greater improvements in the material conditions of human life. The 68-year life expectancy of the 1970s steelworker was almost fifty percent longer than the 46 years of his 1900 predecessor, and his mid-century lifespan has been eclipsed in turn by the current 76 years.

The labor market is changing in ways that go far beyond the automation that worried my father. A fundamental transformation of the structure of jobs and the very content of work is taking place, enabled by interlinking technologies of cloud computing and the Internet of Things, driven and controlled by the machine-learning algorithms of artificial intelligence.

New mechanical technologies like electric cars and robots combined with the executive function capabilities of artificial intelligence are squeezing the human labor market in a pincer grip. New products and processes require new technical skills, while cognitive and control functions that used to be unique to humans are being taken over by self-teaching cyber systems. Robotic Process Automation (RPA) will, by some projections, eliminate 40% of the world’s jobs within 15 years. The speed and direction of change are driving companies to develop in-house strategies for upskilling, reskilling, retraining and new-skilling to “optimize the workforce” by upgrading existing workers or hiring new ones with the speculative skill sets of a market so mercurial that job descriptions written yesterday are obsolete by tomorrow. Economists call this relentless churn “creative destruction.” My father called it putting people out of work.

The skills needed to survive in this performance pressure cooker go beyond traditional degrees and technical competencies to encompass attributes like creativity, interpersonal skills, adaptability, flexibility, and capacity to continue learning. So-called “soft skills” associated with the liberal arts like empathy, cross-cultural competency, critical thinking, teamwork and oral and written communication are regaining value. As machines take over production tasks, as robots become self-teaching and electric cars self-driving, humans have to scramble up the functional pyramid to the higher conceptual ground of process development and problem solving.

The labor value proposition is shifting from implementation to innovation, from productivity to creativity.

Our workforce development system, K-12 and higher education, will be forced to adapt to the volatile demands of this fourth industrial revolution. The foundational language and math skills on which higher order skills depend are more critical than ever for individual survival in the labor market and for our collective survival in the global economic cage fight. It should alarm us that the US ranks 19th in the world in the percentage of 25 to 29 year-olds who have bachelor’s degrees (35.6%). This age group is a bellwether of workforce quality because their tenure in it will be long. Twenty years ago, we were number one. Where will we be twenty years from now?

Heavy industry laid the foundations of its own obsolescence. Blue collar workers built the skyscrapers in which white collar technocrats invented the post-industrial economy.

The mills of the Calumet are producing twice their output of the 1970s with a quarter of the labor force. The jobs don’t look anything like the grimy millrat labor of my dad’s time. Today’s oil and steel workers sit at computer consoles digitally controlling the stills and furnaces. Robots do much of the dirty and dangerous work without gloves or hard hats. Fair trade coffee is served in the cafeteria. No one stops at the diner anymore.

Twilight can be dusk or dawn. It’s dusk for the old industrial workforce, but it can be dawn for a new workforce with the skills required by the new economy. School is starting this week. Nine out of ten of America’s young people are sitting down at desks and terminals in public schools. Fifty million public school students, our workforce in training, are writing the next chapter of our history. Their knowledge and skills—not petroleum or iron ore—are the raw materials of our future. We’d be wise to invest as much capital in their development as Rockefeller and Morgan did in oil and steel.

“Labor’s Twilight” was first posted on Labor Day 2018. Updated for Labor Day 2019.

Gary Kaplan is the executive director of JFYNetWorks.

Matthew Kaplan is a Chicago-based photographer. His work can be viewed at matthewkaplanphotography.com