Bright stars among a vast constellation

by Joan Reissman

Black History Month is a time to contemplate the complex history of Black people in America and Canada. It is a time to celebrate successes and contributions, but it is also a time to acknowledge the obstacles many Black people have had to overcome. This month JFYNetWorks highlights Black scientists. Many people have become aware of Black scientists’ contributions from the movie Hidden Figures and Neal deGrasse Tyson’s books and TV show. The fame of George Washington Carver is long-established. However, there are many Black contributions to science that are hardly known. It would be impossible to cover them all, but I will profile a few breakthroughs and inventions that have become essential parts of modern life.

Alice Ball, M.S. (1892-1916)

Few today have heard of Alice Ball. Although she died at age 24, she made an important contribution in her short life– the first successful treatment for leprosy. She did not get credit until many years after her death. Alice Ball was the first woman and first Black person to receive an M.S. in Chemistry at the University of Hawaii, in 1915. Hawaii happened to house a leper colony. (Since it is a highly contagious disease, the standard medical practice was to confine lepers to treatment facilities in isolated areas.)

Alice Ball also became the University of Hawaii’s first woman chemistry professor. In her research, Ball experimented with using oil from the chaulmoogra tree. This oil had been used to treat leprosy in India and China. Ball reformulated the oil so that patients could be injected directly. This treatment was used for many years until sulfone drugs were introduced in the 1930s. Tragically, Alice Ball’s life was cut short by a lab accident. She died from complications after inhaling chlorine gas. She accomplished so much in her short life. Who knows what she might have contributed had she lived beyond the age of 24.

Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alice_Augusta_Ball.jpg

Percy Julian, Ph.D. (1899-1975)

Percy Julian is a shining example of what a person can accomplish with grit and perseverance. Julian was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on April 11, 1899, the son of a railway clerk and the grandson of slaves. He did well in school but there was no public high school for African Americans in Montgomery. Julian graduated from an all-Black normal school inadequately prepared for college. Even so, in the fall of 1916, at the age of 17, he was accepted as a sub-freshman at DePauw University in Indiana. This meant that in addition to his regular college courses he took night classes at a high school. He also had to work in order to pay his college expenses. Nevertheless, he excelled.

He graduated college and then accepted a position as a chemistry professor at Fisk University. Julian received a scholarship from Harvard and completed a master’s degree in chemistry, but Harvard would not admit him into the Ph.D. program. Determined not to let any obstacles divert him from his goal, he was admitted to the University of Vienna.

In 1931, after he received his Ph.D., Julian returned to De Pauw where he continued his research and developed a successful treatment for glaucoma. But the university refused to make him a full professor.

Having received international acclaim for his discovery, he decided to seek a position as a researcher for a biomedical corporation. After many rejections, he became the lab director for the Glidden Company. He continued his research on soybean products and developed AeroFoam, a product used for fire extinguishing during World War II. Julian also synthesized many other drugs we use every day, including synthetic hormones and cortisone. The next time you get a cortisone injection for an achy joint, remember to thank Percy Julian.

DePauw University Archives and Special Collections, https://www.depauw.edu/news-media/latest-news/details/22969/

Patricia Bath, M.D. (1942-2019)

Glaucoma wasn’t the only eye problem solved by a Black scientist. Laser treatment for cataracts was developed by Dr. Patricia Bath. Dr. Bath grew up in New York City and earned a degree from Hunter College. She went on to an M.D. at Howard University and, after graduating, worked on a fellowship at Columbia. At Columbia, Dr. Bath began her lifelong interest in improving vision. While an intern at Harlem Hospital, she noticed that a high proportion of Black patients had vision problems. To address this disparity, Bath was the first doctor to develop the field of community ophthalmology, a field designed to improve and diagnose vision problems in underserved populations. She helped develop outreach programs by using volunteers to visit community centers and provide basic screenings. Because of Dr. Bath’s efforts, ophthalmologic surgery became a full department at Harlem Hospital.

In 1974 Dr. Bath moved to UCLA and became the first female professor in UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute. She then moved to Europe for better opportunities and began research on laser technology. She eventually returned to Harlem Hospital, where her research led to the invention in 1981 of the laserphaco, a method for using lasers to restore vision to patients suffering from cataracts. She finally received a patent for her invention in 1988. The laserphaco is still used today. If you should need cataract surgery at some point, don’t forget Dr. Patricia Bath, the Black woman who made your surgery possible.

Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricia_Bath#/media/File:Patriciabath.jpg

Jane C. Wright, M.D. (1919-2013)

Have you ever had a friend or relative who was treated with chemotherapy? You can thank Dr. Jane C. Wright for her trailblazing research. Wright needed only to look to her family for inspiration and motivation for success. Several people in her family were doctors, including her maternal grandfather who started life as a slave and graduated from Meharry Medical College.

Dr. Wright decided to follow their example and attended New York Medical College. She received her degree in 1945 and completed her residency at Harlem Hospital. After practicing for a short time, she joined her father’s cancer research team at Harlem Hospital.

When Wright joined her father in 1949, chemotherapy treatment was not widely used or understood. Doctors didn’t understand much about the treatment or therapeutic dosage. Dr. Wright and her father were among the first medical researchers to treat cancer with a variety of new drugs. They began testing drugs to combat leukemia and lymphoma. Wright also pioneered the testing of cancer drugs on human tissue. This methodology, still used today, was far more predictive of results.

Dr. Wright was not the type to be satisfied with simply producing potential treatments. She wanted to make sure people would actually receive the benefit of her innovative drug therapies. She became a founding member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, an organization dedicated to giving more people access to medical care.

In that same year, 1964, President Johnson appointed Wright to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. She also served as Professor of Surgery, Head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and Associate Dean at the New York Medical College. In 1971 Dr. Wright was appointed the first female President of the New York Cancer Society.

In her illustrious career, Dr. Wright published many articles, but the most important thing to her was helping the average citizen benefit from her research and life-saving treatments. We owe a great debt to this pioneering Black woman scientist.

Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jane_C._Wright#/media/File:Jane_Cooke_Wright.jpg

Jewel Plummer Cobb, Ph.D. (1924-2017)

Jewel Plummer Cobb was another Black female scientist who made important contributions to chemotherapy treatments. During several periods of her career, Cobb worked with Jane Wright. Both women advanced the science of medicine through innovative methods and discoveries. There are other parallels between them. Cobb also had many doctors in her family. Her grandfather was also born into slavery, and he earned a medical degree from Howard University. Cobb’s father also became a doctor.

Jewel Cobb first attended the University of Michigan. But she felt isolated so she transferred to Talladega College. After Talladega, Cobb applied to New York University. She was accepted but was not given a teaching fellowship until she visited the university. Cobb convinced NYU to support her training with a fellowship and she completed her Ph.D. in cell physiology.

In graduate school, Cobb became interested in pigment formation and began her research on melanin. Her interest in melanin would lead to important discoveries in treating skin cancer.

After graduating from NYU, Cobb began a fellowship at Harlem Hospital and worked with Dr. Wright. Both women were interested in testing cancer drugs on human cancer cells. This methodology was very innovative during the 1950s.

After her fellowship, Cobb started her own lab at the University of Illinois. Cobb continued her interest in melanin and its relationship to skin cancer. In 1954 she returned to Harlem Hospital and continued her work with Dr. Wright. Both women were pioneers in using patient biopsies in vitro. Cobb was one of the first scientists to establish the relationship between light exposure and melanin.

Cobb was also an activist. She published a paper that addressed discrimination against women in science and continued to act as an advocate for more professional medical opportunities for Black students. In an interview, she said, “I think I’d like to be remembered as a Black woman scientist who cared very much about what happens to young folks, particularly women going into science.”* There’s no doubt that Dr. Jewel Cobb accomplished this goal and will be remembered for her contributions to science and for her advocacy.

* https://www.jax.org/news-and-insights/jax-blog/2018/may/women-in-science-jewel-plummer-cobb

Connecticut College, “Koiné 1970” (1970). Connecticut College Yearbooks. 50.

https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/yearbooks/50, https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1050&context=yearbooks

Daniel Hale Williams, M.D. (1856-1931)

Today we take for granted that we will get open heart surgery if we need it. We have Dr. Daniel Hale Williams to thank for performing one of the first successful open-heart surgery operations.

Williams started out as a shoemaker’s apprentice. But sewing shoe leather wasn’t for him, so he became a surgeon’s apprentice. He was talented and liked medicine so he went to Chicago Medical School where he received his M.D. in 1883 and opened his own practice in Chicago.

Dr. Williams was responsible for many innovations. One of his earliest contributions was to advocate for sterilization during medical procedures. Very little was understood about germs in the 1880s, but Williams had read studies by Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister. He began to sterilize equipment and successfully reduced germ transmission during procedures.

Dr. Williams also wanted to provide more opportunities for hospital care and training. He established Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses in 1891. This hospital had the first interracial staff in the country. Provident Hospital was the first training school for Black nurses. Any patient could get care at Provident Hospital- regardless of race or income. He also founded the first association for Black medical professionals, the National Medical Association.

Dr. Williams should be recognized for performing one of the first successful open-heart surgeries. It should be remembered that we didn’t have the same level of anatomical knowledge and procedures in the 19th century. Dr. Williams treated a patient by cutting deeper into the chest and repairing an artery. The patient survived and lived 20 years after the surgery.

Williams lived to be 75 and worked at several other hospitals during his career.

CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0), Public Domain Dedication, The National Library of Medicine http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101448033, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Hale_Williams#/media/File:Daniel_H._Williams.jpg

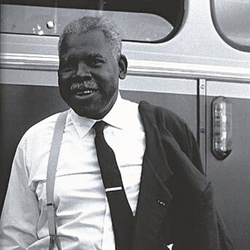

Hildrus Poindexter, M.D., Ph.D. (1901-1987)

Hildrus Poindexter began life in rural Tennessee, but it would require a large wall to display all the degrees he received in his life. Poindexter’s parents were enslaved and then became tenant farmers. He started his post-secondary education at Lincoln University and went on to earn many advanced degrees. He was the first Black American to receive an M.D. and a Ph.D. in addition to a Master’s in Public Health.

After finishing his graduate work, Poindexter became the head of Howard Medical College in 1936. When the U.S. entered World War II, he joined the military and became instrumental in treating soldiers who suffered from tropical diseases. Dr. Poindexter earned a bronze star for his role in reducing malaria and schistosomiasis during the war. After the war, Poindexter joined the U.S. Public Health Service and traveled all over the world. During his tenure at U.S.P.H.S, Poindexter was appointed director of the Mission to Liberia.

After 30 years of service, Poindexter returned to Howard University and used his experiences in the field to teach courses in community health. Poindexter also detailed the experiences of his storied life in his autobiography, My World of Reality. He discussed his tough road to success and the racism he faced while in the military. He never got discouraged as he pursued his goals. He devoted his life to improving outcomes of tropical diseases and advancing medical treatments. The world is a better place for his perseverance.

I hope you have learned a few things about these Black scientists. There are many others who haven’t received the credit they deserve. As you think about their discoveries and inventions, consider that these scientists and many others stand as models of what is possible.

CC by 4.0, Creative Commons and Attribution, Hildrus Poindexter. Photograph by L.J. Bruce-Chwatt, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hildrus_Poindexter._Photograph_by_L.J._Bruce-Chwatt._Wellcome_V0028003.jpg

Next month we will focus on women scientists and the challenges they faced, and still face.

Joan Reissman is a Learning Specialist with JFYNetWorks.

Other posts authored by Joan can be found here.

HOW ARE WE DOING? In our pursuit to serve up content that matters to you, we ask that you take a couple of minutes to let us know how we’re doing? Please click here to be navigated to our JFYNet Satisfaction Survey. Thank you!