by Paula Paris

William Monroe Trotter 1872 – 1934

“For every right, with all the might”

(Motto of the Boston Guardian)

On Humboldt Avenue in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in the heart of what was once a thriving middle-class African-American residential and business neighborhood, sits the William Monroe Trotter K-8 School, one of two local tributes to its namesake. The other is the home Trotter once owned on Sawyer Avenue in Jones Hill, Dorchester, where he and his wife lived from 1899 to 1909 and which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976. Boston-bred Trotter was a major civil rights activist and journalist in the early twentieth century, whose legacy has largely faded away. There are no monuments preserving his likeness.

Monroe Trotter, his parents, and two sisters were among very few Black families living in Boston’s Hyde Park neighborhood in the late 19th century. Monroe was a brilliant, hard-working and affable student. He was senior class president and valedictorian of Hyde Park High School in 1891. He attended Harvard College where he was elected Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year (the first African-American so honored) and graduated magna cum laude with a degree in International Finance in 1895. This was one year before the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Jim Crow principle of “separate but equal” in Plessy v. Ferguson. While his white classmates eased seamlessly into Boston’s business and banking establishment, that opportunity was closed to Trotter. He worked for several years in his father’s successful real estate business, acquired multiple properties, and launched his own successful real estate brokerage firm. But social justice activism would be his true calling.

Monroe – known as Mon to his close associates – and Geraldine “Deenie” Pindell were friends since childhood before marrying in 1899. She came from a prominent Black family in Everett, with similar social justice views to the Trotters. Her father Charles was an attorney and her uncle William led the struggle for Boston school integration in the 1850s. Deenie attended business school and worked as a bookkeeper before joining her husband as associate editor and business manager of the Boston Guardian, the newspaper he co-founded in 1901. But Deenie was also an activist and philanthropist in her own right, supporting the rights of Black World War I troops, raising funds for St. Monica’s Home for needy women and children, and participating in the Women’s Anti-Lynching League. Although both Deenie and Mon came from elite privileged families, they sacrificed the comforts of their privilege to be partners in the fight for racial justice and equality. They also urged other similarly advantaged Blacks to invest more of themselves in the cause. Deenie died young at 46 of influenza during the 1918 pandemic. Monroe published a tribute in the Guardian, calling her his “fallen comrade” who gave her life “for the rights of her race.”

friends since childhood before marrying in 1899. She came from a prominent Black family in Everett, with similar social justice views to the Trotters. Her father Charles was an attorney and her uncle William led the struggle for Boston school integration in the 1850s. Deenie attended business school and worked as a bookkeeper before joining her husband as associate editor and business manager of the Boston Guardian, the newspaper he co-founded in 1901. But Deenie was also an activist and philanthropist in her own right, supporting the rights of Black World War I troops, raising funds for St. Monica’s Home for needy women and children, and participating in the Women’s Anti-Lynching League. Although both Deenie and Mon came from elite privileged families, they sacrificed the comforts of their privilege to be partners in the fight for racial justice and equality. They also urged other similarly advantaged Blacks to invest more of themselves in the cause. Deenie died young at 46 of influenza during the 1918 pandemic. Monroe published a tribute in the Guardian, calling her his “fallen comrade” who gave her life “for the rights of her race.”

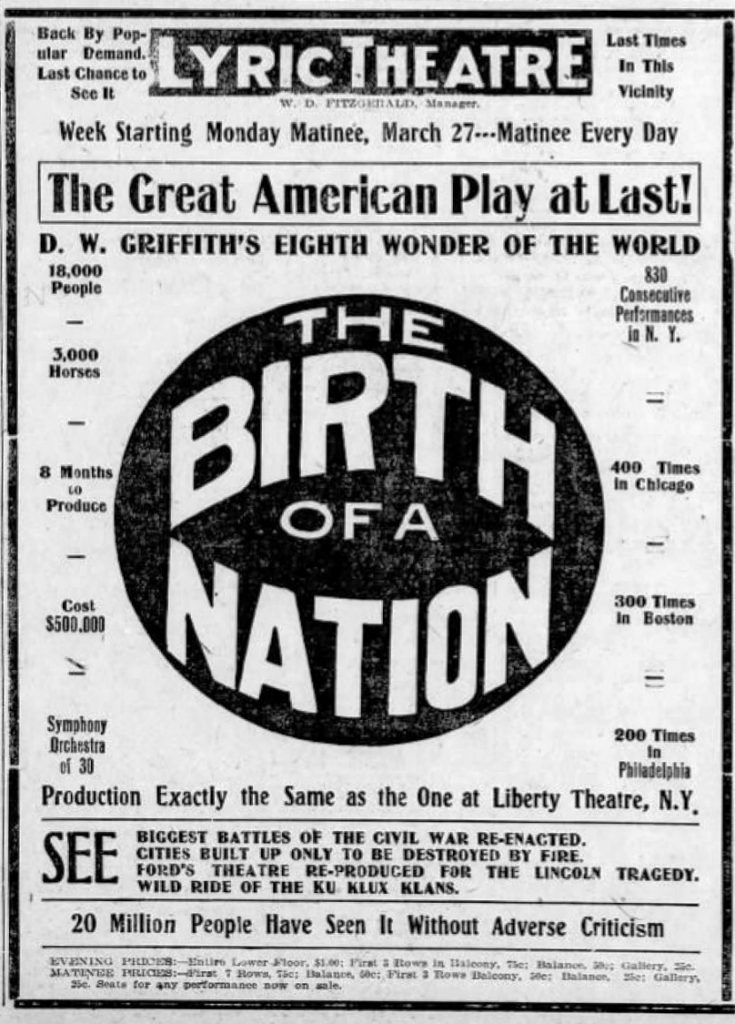

Trotter’s activism emerged in college, first as a founding leader of the Total Abstinence Club (to curb student drinking), followed by a protest against the segregated barber shops in Cambridge. He was keenly aware that education and personal wealth accumulation, though important, did not create fundamental change in the inequality of Black people in America or globally. He would lead many demonstrations, including a boycott of D.W. Griffith’s racially derogatory film “Birth of a Nation” and a nationally publicized in-person demand to President Woodrow Wilson to desegregate the federal workforce, a protest of the segregation policy Wilson had initiated in 1913.

Trotter’s activism emerged in college, first as a founding leader of the Total Abstinence Club (to curb student drinking), followed by a protest against the segregated barber shops in Cambridge. He was keenly aware that education and personal wealth accumulation, though important, did not create fundamental change in the inequality of Black people in America or globally. He would lead many demonstrations, including a boycott of D.W. Griffith’s racially derogatory film “Birth of a Nation” and a nationally publicized in-person demand to President Woodrow Wilson to desegregate the federal workforce, a protest of the segregation policy Wilson had initiated in 1913.

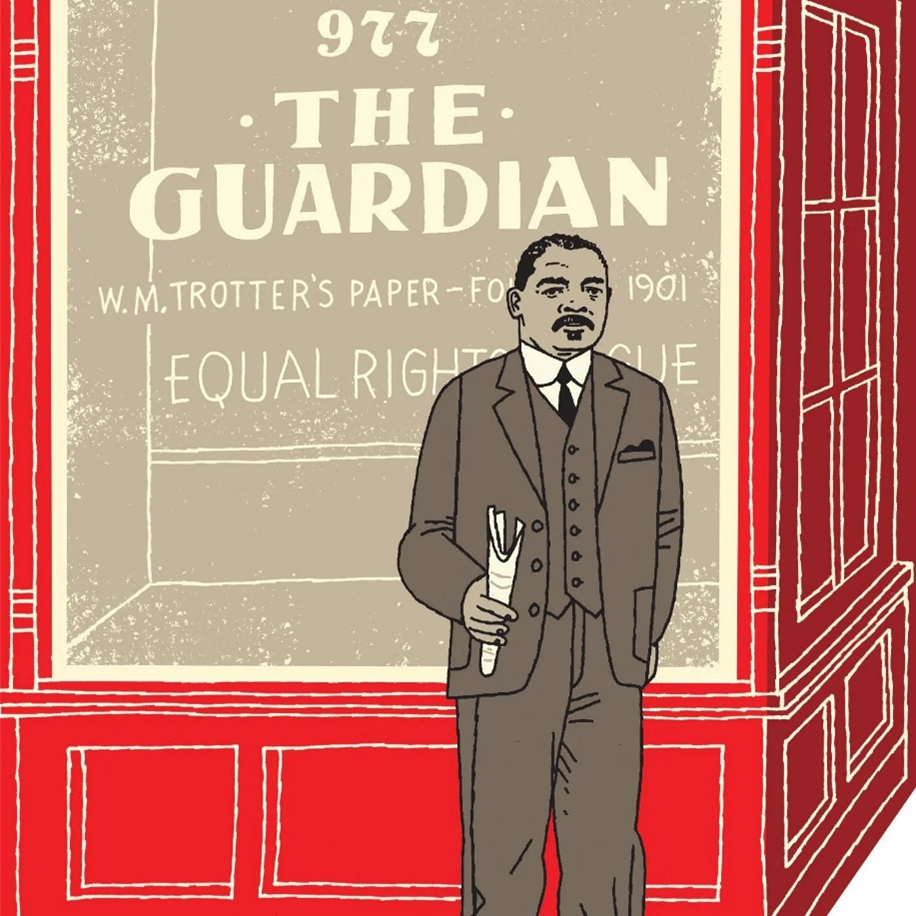

In 1901 Trotter and George Washington Forbes founded the Boston Guardian. The paper’s motto, “For every right, with all thy might,” reflected the view that racial equality and civil and political rights could not be gained in stages, but required relentless protest and civil disobedience. He rejected what he considered the conservative incrementalism and “accommodationalism” of Booker T. Washington, and the gradualism of the NAACP. Trotter routinely lambasted Washington in the paper about the many issues on which they disagreed. The Guardian chronicled a potpourri of local political, social and cultural gatherings, marriages, promotions, births and deaths in the Black communities of Greater Boston. It selected national and international news of the Black Diaspora, as well as announcements of lynchings in the South. From its perch on Tremont Row (now Government Center) in the same block as Boston’s premier newspapers, the Globe and the Herald, and in the same building that had housed William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator, the Guardian became a platform for radical protest.

While the Guardian often included appeals for funds to support legal defenses, unlike most publications the paper neither sought nor accepted advertising for tobacco or alcohol products – a risky policy for someone with Trotter’s prior business experience. He banked on deriving revenue from sales and subscriptions. At the turn of the century, Boston could boast one of the nation’s highest literacy rates among Blacks and the largest number of Black professionals – doctors, lawyers, dentists and small business owners and entrepreneurs. There seemed to be a vibrant market for a Black newspaper.

Although Greater Boston was a hub of anti-slavery activism, African-American intellectualism and progressive political thought, Trotter reminded Black citizens and white allies that racial discrimination and segregation were not limited to the southern states, but were fully present in the North, though manifested in different ways. He believed that building coalitions across socio-economic classes would be the most effective strategy to combat racism and achieve complete equality.

The Guardian flourished for several years with local and national readership. But the paper was never profitable and it drained Trotter’s financial assets as his declining popularity, shifting demographics, and the Great Depression undermined its standing and its finances. Monroe’s sister Maude Trotter Steward continued publication of the Guardian for twenty years after her brother’s death.

Trotter died on his 62nd birthday, April 7, 1934, in a fall from the roof of the Cunard Street boarding house where he had spent his waning years. He is buried next to his beloved Deenie in Fairview Cemetery, Hyde Park, which is also the final resting place of former mayor Thomas Menino.

William Monroe Trotter should be remembered as a brilliant man who held steadfastly, with all his might, to his calling to build a just society. His relentless pursuit of that ideal made him a controversial figure. He was a champion of social justice and systemic reform, a visionary who foreshadowed leaders and movements yet to come, from the Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s and 60s to Black Lives Matter.

In 1984, the William Monroe Trotter Institute was established at UMass Boston “to address the concerns of Black communities in Boston and Massachusetts through critical research, public advocacy and community engagement.” He would have considered this center of inquiry and activism the most fitting of all monuments, a living embodiment of the cause and commitment that drove his restless, relentless life.

In 1984, the William Monroe Trotter Institute was established at UMass Boston “to address the concerns of Black communities in Boston and Massachusetts through critical research, public advocacy and community engagement.” He would have considered this center of inquiry and activism the most fitting of all monuments, a living embodiment of the cause and commitment that drove his restless, relentless life.

Paula Paris is Deputy Director of JFYNetWorks. JFY’s Board Chairman Otis Gates was co-founder of the Bay State Banner, Boston’s second Black newspaper, in 1965. The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Kerri Greenidge, whose definitive biography “Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter” has sparked renewed interest in the subject.

Image attributions:

Header image: Date 1915: Source-Dickinson College: http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/35232 , source citation: Boston (MA) City Council, Exercises at the Dedication of the Statue of Wendell Phillips, July 5, 1915 (Boston: City of Boston, 1915), 11. (Author Published by Boston City Council)

Licensing Public domain: This media file is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired.

Geraldine “Deenie” Pindell Trotter: The Crisis, Vol. 17, No. 2. (December, 1918).

Birth of a Nation: The Allentown Leader, 18 March 1916 Via https://www.newspapers.com/, Author Lyric Theater 23 North Sixth Street, Allentown, PA

The Guardian: Front page of The Guardian, July 26 1902 | Date:14 July 2020, Source: Own work, Author: XelaWho Licensing: I, the copyright holder of this work, hereby publish it under the following license: Creative Commons. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Trotter Illustration: UMASS Boston official twitter account: https://twitter.com/trotterUMB. Attribute: Illustration by Paul Rogers, published: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/11/25/the-legacy-of-a-radical-black-newspaperman. Citing ‘Educational’ Fair Use as described here: https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/more-info.html

HOW ARE WE DOING? In our pursuit to serve up content that matters to you, we ask that you take a couple of minutes to let us know how we’re doing? Please click here to be navigated to our JFYNet Satisfaction Survey. Thank you!