by Eileen Wedegartner, Blended Learning Specialist

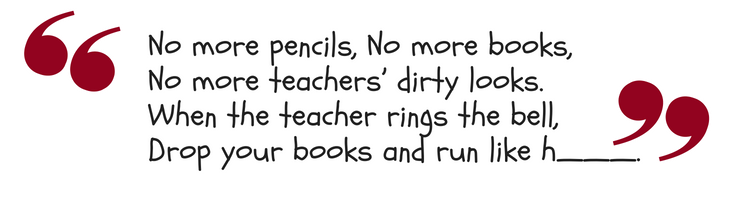

I fondly recall a ragged rhyme that kids used to chant on the last day of school. Every adult of a certain age knows some version of it, but the one we always bellowed was:

Only the most daring or naughty would speak the last word. The rest of us just let it hang in the air as we fled toward the fleet of yellow buses that would ferry us away from the stifling chalk dust-filled confinement of desks and books and droning teachers to the sun-splashed freedom of beach balls, bikes, and the soothing chimes of the ice cream wagon.

As the youngest child in the neighborhood, I would come home to the blare of Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out” with its defiant extension of “No more teachers” and Pink Floyd’s taunting “We don’t need no education” from the older kids’ cars and boom boxes. The days stretched endlessly before us and new discoveries were always just around the bend. We read whatever books looked interesting, nothing “assigned.” No one would ever test us or demand proof that we actually read the book. Some kids did not read any books at all. Instead they gorged themselves on drive-in summer movies and trashy teen magazines.

We did practical math, not math practice. Sometimes it was engineering, like when we learned that not all makeshift board bridges would support the weight of every kid and we needed reinforcement for the bigger kids to get across the stream. (This is an actual MCAS question.) Other times we measured old sheets and cut them up for curtains in a fort. We discovered that the surplus paneling we found in the basement from when our father finished the playroom could not be used as floor boards in a fort but worked fine as a wall or a flimsy door and could also be used as roofing. We took swimming lessons, raced to the last dock on the lake, timed the quickest bike route home and learned to calculate how much change would have to jingle in our pocket for one Italian ice.

By the time we got back to school, Labor Day had passed, and we were ready to get back to the labor of being students again. With that return came the inevitable review of material from the previous year. We needed to reactivate the muscle of memory to recall math facts and practice writing and assigned reading. As a child and even as a young adult, I was fine with that. There was plenty of time to master everything and anything.

When I recall those times, I understand why so many people say, “kids are over tested,” “there should not be longer school days,” “school should not start before Labor Day” or “school goes way too late in the year.” But as an adult, a mother and an educator, I realize that mastery takes time. Though I indulge my nostalgia for those “school’s out” days, I know that the world has changed, and things cannot be as I fondly remember them.

There may have been time for students of yesteryear to lose some learning over the summer, but those leisurely times are gone. It was not that long ago that young people could graduate from high school and find a job with a career ladder that would lead up to a sustainable income. They could go to work in a factory or a bank and pay the rent, buy food and have money left over for entertainment. Higher education was an option but was not necessary for survival. That is no longer the case.

In 2014 Pew Research published the article “The Rising Cost of Not Going to College.” The disparity between high school graduates and college graduates was staggering: median annual earnings of $45,500 for a bachelor’s degree versus $28,000 for a high school diploma. Even more shocking was the percentage of high school graduates who live in poverty: 21.8% vs. 3.8% of bachelor’s degree holders. The numbers have changed in subsequent years and many other studies have appeared, but the gaps have not narrowed.

If a child has any of the officially recognized barriers to learning (FLNE, ELL, SPED, Economically Disadvantaged) summer is no longer a time of lazy days but an opportunity to continue and supplement learning so that the child does not fall behind in the cumulative sequence of mastery.

As a parent of a student with a learning disability, I have eagerly capitalized on programs that offer academic enrichment through structured math and reading activities that prevent learning loss and support continuing gains. Needless to say, the lucky scholar in question does not welcome the opportunity with the same enthusiasm as his parents. Yet a little persuasive framing of how this program will help build his skills and confidence underlined by a promise that it would not eat up too much time on any given summer day swayed him grudgingly to get on board. We sweetened the formal learning with some of my old-fashioned practiced math: building a bridge and a fort and mapping the neighborhood for fun.

I’d be only too happy to forget extended school days and years and summer learning time and all the rest. But in a world that demands more knowledge and skill than ever, the need for children to be continually learning is inescapable. Whether a formal school program, a camp, a recreational program, a sport or online activity, continuous skill building is critical. School may be out for the summer, but education doesn’t take vacation anymore.

Sorry, Alice.